Silver and Gold

On the 25th anniversary of *The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay*

So far it had been kind of a rough year. In April, after a bad amniocentesis result, Ayelet and I had chosen to terminate a much-wanted pregnancy in its eighteenth week; a boy who would have been our third child. The baby’s would-be older brother, not yet three, had suggested we call him Rocketship, and that turned out to be all the name he was ever going to get. There were still four of us, just like there had been, but inside that square, I no longer felt so invulnerable; somehow it no longer felt quite like a square.

To mark Mother’s Day, I planted a flowering plum tree in front of our house, but it didn’t take. On Father’s Day, I was in Russia, on a week-long State Department-sponsored cultural tour of Moscow, St. Petersburg, Helsinki, and Vilnius. Back in Berkeley, there were only three of them. “Is Daddy dead?” our son asked Ayelet, with a toddler’s off-hand gravity. She reassured him that no, Daddy was in Russia. “Is Russia the dead place?” he said.

Outside Vilnius I visited the town of Nemenčinė, known to my maternal grandfather’s family as Nementchin. In its town square my kind and earnest Lithuanian guide leapt out of our hired car and began gently accosting people, asking if they knew anything about the Jews who used to live in the town. One man pointed to a low brutalist blockhouse—the cinema—where, he had heard, there once had been a synagogue. Another, much older man gave our driver directions to a spot, on a road outside town, where the woods thinned, and where I spent half an hour wandering around in a light drizzle, looking in vain for the putative Jewish cemetery, and crying. I astonished my guide, I think, with the vehemence of my grief. Then the drizzle turned to a downpour, and as we ran back to the car I tripped and fell, flat on my belly, over something that turned out to be a jagged chunk of gray dolomite, engraved with Hebrew characters. The headstones were everywhere, in those woods, once you knew to look for them in pieces, underfoot.

And now it was September, and my latest novel was coming out, and I had no idea what to expect, partly because I didn’t feel ready to resume the having of expectations, but mostly because after nearly five years I still struggled to describe the book to people in a way that did not make their eyes go glassy with pity or concealed alarm.

One night a few years earlier, at the MacDowell Colony (as it was then known1), I had sat down to dinner with three other Fellows, all recent arrivals like me. We had gone around the table, making conversation MacDowell style, and it turned out all four of us were there to work on novels. The writer who went first had offered a brief description of her project—the story of a pair of siblings on the run from slave-hunters before the Civil War. It sounded fascinating, and important, and I felt a mounting apprehension as we continued around and the other two writers described their novels, which also dealt with self-evidently substantial matters. Deforestation, child soldiers, that sort of thing. Finally it was my turn, and I hesitated, hoping we might be interrupted by an announcement, or the appearance of dessert.

“I’m writing about two guys in the early days of the comic book business,” I finally acknowledged. “Who invent a superhero.”

People, especially people in movies and tv shows, often say, bitingly, “Do you even hear yourself?” I heard myself. And then I heard nothing at all. In movies and tv shows, as well, someone in a social situation that makes them feel insecure will say something gauche or inappropriate, and then a deep, pitying silence descends; but until that night at MacDowell, I had never seen it happen offscreen.

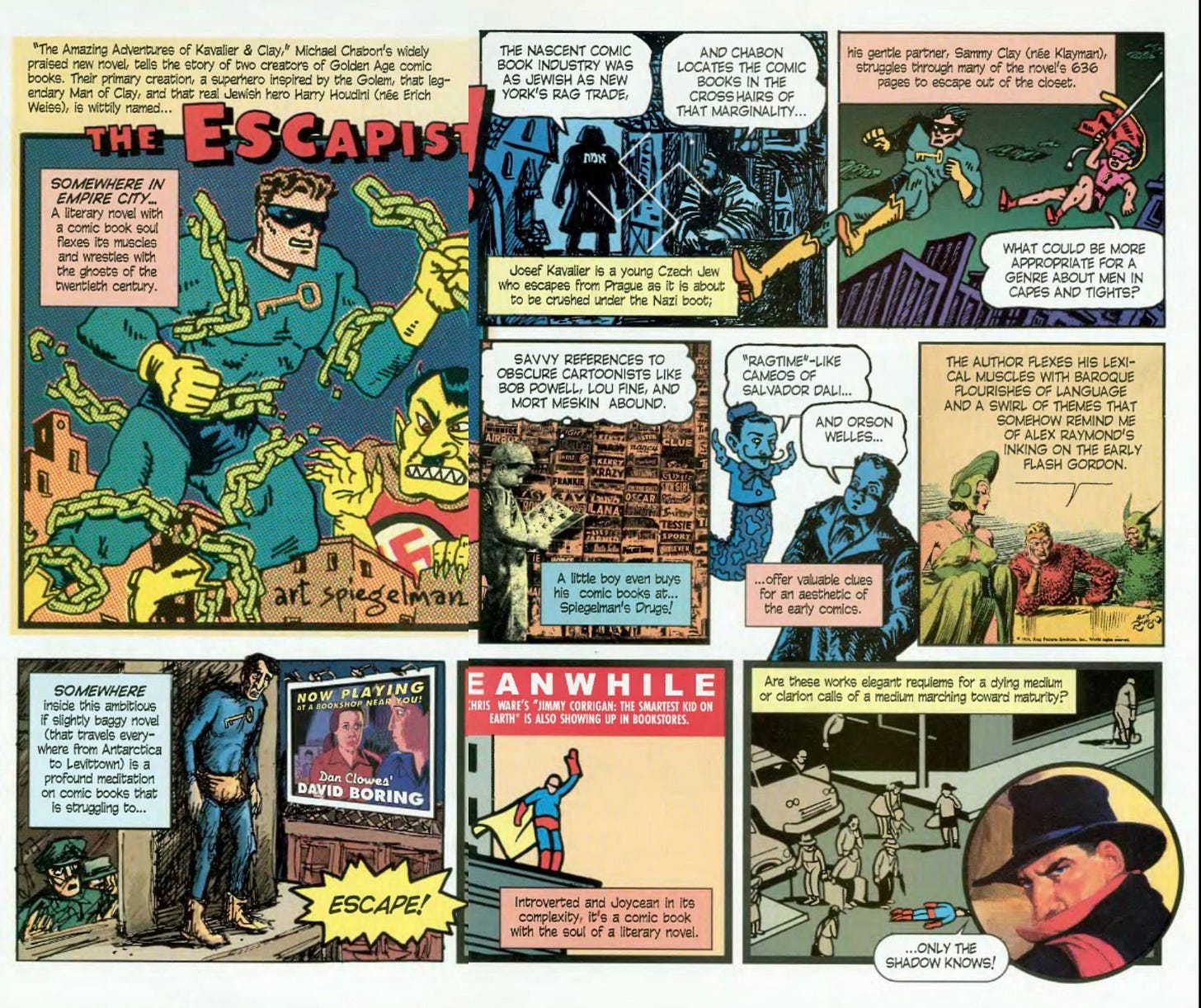

All my life, comic books had been uncool, and I had been uncool for liking them. That was okay; I was used to it. But it turned out that there was something even more uncool than liking comic books—superhero comic books, especially—and that was taking them seriously. Sure, Art Spiegelman’s Maus had been awarded a Pulitzer Prize, back in 1992, but people called it a “graphic novel,” not a “comic book,” and it was a memoir, written and drawn by the son of Holocaust survivors, and the prize committee had felt obliged to create a nonce category in order to award it a Pulitzer, as much to quarantine it, I thought, as to praise it. There were no costumed superheroes in Maus. In 2000, an Oscar-winning superhero film lay eighteen years in the future, and costumed superheroes were still the most uncool thing of all. If you presumed to take them or the work of their creators seriously, the culture had a name for you: Comic Book Guy.

No writer, as far as I knew, had ever published a novel in which superhero comic books and the lives and sundry aspirations of the people who created them were taken seriously. And as, over the course of the previous five years, I’d gone around killing conversations left and right with my attempts at summarization, inspiring pity and unease among friends and strangers alike, it had begun to seem that there might be sound reasons, both artistic and commercial, for this collective silence on the part of every novelist since 1938.2

My German publishers, for example, had done very well with my first novel, and okay with my second, but they’d initially passed on the manuscript of Kavalier & Clay. My UK publishers had also turned it down, until an editor there chanced to get hold of an abridgment that had been prepared for the audiobook edition (abridged audiobooks were more common at the time, probably due in part to the production cost incurred by the need for a greater number of CDs or cassettes). My UK publishers had felt bad about turning down the book, and now they signaled their willingness to bring out this abridged edition; my German publishers caught wind of the idea, and had immediately jumped on board.

Apparently there was one thing even less cool, at least from the commercial standpoint, than a “serious” novel about superhero comic books and the lives and sundry aspirations of the people who created them, and that was a really long novel about superhero comic books and the lives and sundry aspirations of the people who created them.

My US publishers, I could tell, had their own doubts about the book’s length—its sheer bulk; they had printed it on some kind of fine, ultra-thin “Bible paper,” and set the text in a very small point size. Also—a less subtle clue—as the book went into production, my editor had suggested and strongly encouraged the deletion of two chapters in its sixth and final part3, which would bring the final page count below 650. Neither chapter was crucial to the plot, perhaps, but they were strong and useful chapters, helping in the first instance to give context and texture—to “sell”—the oppressive repression of Sam Clay’s closeted, postwar-Long Island existence and, in the second, easing both the reader and Joe Kavalier, who had spent the postwar years on the run and in traumatized hiding, into believing that he retained the capacity to do anything as complicated as coming home.

From the time that I first read Watership Down, at age 11, forcing myself to slow down, dreading the impending bereavement of the approaching 478th and final page, I have never understood what I soon discovered to be a widespread apprehension among other readers: that a novel could be “too long.”4 But with editors in Europe waving abridgments around, and my US editor looking everywhere for possible cuts, I could hardly deny that the phenomenon was real. They were afraid that nobody was going to buy the gigantic thing. Out went the chapters.5

It would not be entirely fair or accurate to say that when the book came out, on September 19, 2000, it was a flop. The reviews were mostly very good, even excellent, written by smart critics like Donna Seaman, Ken Kalfus, Daniel Mendelsohn and, of all people, Spiegelman himself, charitably overlooking the fact that I had named the book’s irascible, comic-book-hating Long Island druggist “Mr. Spiegelman.”

I had some good turnouts at the readings and signings I did on book tour, and, gradually, word seemed to spread among people who were not immediately put off by its subject matter, and its heft. In particular, I was gratified to discover, the book was immediately embraced by the toughest, nit-pickiest, gatekeepingest audience of all: Comic Book Guys.

But for a while after publication, its path seemed shadowed, somehow. Unlucky. For mysterious reasons the first edition was severely short-printed, so that on the magical Sunday when the cover of the New York Times Book Review was Ken Kalfus’s starry-eyed but knowledgable rave, and my mother-in-law went down to her local, Ridgewood, NJ, bookstore to purchase a purely gratuitous celebratory copy (she had already bought a half-dozen or so), she found that it was out of stock, as it apparently was, that week, in every other bookstore in America. Something had gone wrong, too, with orders at Barnes and Noble and the now-defunct Borders chain. The book got nominated for some big prizes, boom boom boom, which was thrilling, but then lost out, pfft pfft pfft. And that was fine, naturally, it was an honor just to have been nominated, etc, except for the part where I had to sit in a big, crowded auditorium, wearing a tight smile, losing and pretending I didn’t care, which objectively was kind of implausible, since I had flown three thousand miles to be there.6

And then, in April 2001, almost exactly a year after Rocketship, the miracle happened. I was out in my backyard studio that morning, answering emails, when I heard the sound of screaming—of Ayelet screaming—coming from the house. She was pregnant again—seven months gone—and I ran so fast and headlong out of the studio toward the house that I tripped, going up the back steps, and barked my shin. I burst in through the back door to the kitchen where Ayelet, holding the cordless phone in one hand, was hopping up and down and shrieking you won the Pulitzer Prize you won the Pulitzer Prize you won the Pulitzer Prize. When I came in she leapt—all five feet and one hundred and fifty pounds of her and the imminent, perfect daughter who would turn up at the beginning of June—into my arms, and I staggered around the kitchen bearing her up, both of us going Oh my God oh my God oh my God. Maybe the grief, at least for now, for this moment, was over. Maybe our luck had changed.

Then Ayelet remembered the phone.

“Hillel!” she said into the receiver. “I’m so sorry!” She it handed it to me. “Michael, it’s Hillel Italie, from the AP!”

“Oh, hello,” I said, remembering having read, somewhere, that it was traditional for the Associated Press to notify the winners of Pulitzer Prizes.

“I gather you heard,” said Hillel Italie.

It has since been decolonized.

The date of Superman’s first appearance.

Included as “Bonus Material” in the most recent paperback edition.

I mean, a too-long bad book, sure; but then you just stop reading it.

I held out against Germany and the UK, however, and eventually they came around.

An ordeal that was partly relieved, at the National Book Critics Circle Award ceremony, when Jim Crace’s novel Being Dead was announced as that year’s winner, and in the brief silence that followed, every person in the New York University Law School auditorium could hear it when the eminent classicist Froma Zeitlin, whom I had met for the first time not ten minutes earlier, turned to her friend Daniel Mendelsohn, down in the fourth row, and intoned, in a classical Jewish-lady stage whisper, Michael was robbed!

I am thrilled and honored to be singing in tonight’s Metropolitan Opera premier of THE AMAZING ADVENTURES OF KAVALIER & CLAY. Bringing your novel to life on the Met’s stage has been an incredible and moving experience, from our first music rehearsal to last week’s final dress. The excitement in the house while creating this work has resonated differently than other premieres at the Met, and I feel grateful to have been a part of it. Happy 25th and congratulations to you, Michael!

It’s hard to believe you doubted yourself about what became your magnum opus, I loved it from my first read and subsequently gifted it to everyone that year for their birthday and I continue to recommend and share it if I discover someone has not had the privilege of reading it, and it is a serious work of profound beauty and power